“The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World” has been a long time coming. The Museum of Modern Art has steadily been acquiring new painting, as a visit to its website will confirm. But for years it has disdained actually saying anything about the state of the medium in exhibition form, and all the while painting has developed actively on numerous fronts.

“The Forever Now,” which opens Sunday and is organized by Laura Hoptman, curator of painting and sculpture at MoMA, considers some of those changes, and it does so with a normal combination of successes and shortcomings, including a lack of daring. Its thesis hinges on the word atemporal, inspired by “atemporality,” which was coined by the science fiction writer William Gibson in 2003. The idea is that, especially in the digital era, culture exists in a state of simultaneity, where all of history is equally available for use.

It could be argued that simultaneity is nothing new: It was once the definition of postmodernism; it also describes the ways artists selectively consider past art alive and useful, and can be a cover for simple derivativeness — a condition not entirely absent from the exhibition.

The terrain the show stakes out is diverse and fairly recent, but also very familiar: The 17 artists represented here are all known, mostly market-approved entities familiar to anyone who follows contemporary art even casually. Nearly all the participants possess résumés dotted with solo shows in smaller museums and at blue-chip galleries, here and abroad; 12 of the artists are already represented in MoMA’s collection.

In short, this exhibition looks far too tidy and well behaved, much as you might fear a show of recent painting at the Modern would look: validating the already validated and ready for popular consumption. For the majority of the museum’s visitors who rarely set foot in commercial galleries, the show may hold surprises and even mild frissons of shock.

And this exhibition may also exceed the expectations even of gallery-scene regulars. Against the odds, it is surprisingly engaging. It gives you plenty to look at, which has become something of a rarity with shows of recent art at the Modern. (It’s when you consider what else could be here that the problems begin.)

The show is actually less predictable than the list of names would imply. It helps that there are new works by several artists. Some, like Julie Mehretu, have pushed into new territory (in her case, from drawing closer to painting, of a decidedly Twombly-esque sort).

If you focus intently, you can get an expanded appreciation of some of the artists. The much ballyhooed young painter Oscar Murillo, for example, shows several reasonably promising new paintings, albeit all lent by one of his galleries, which should have been avoided.

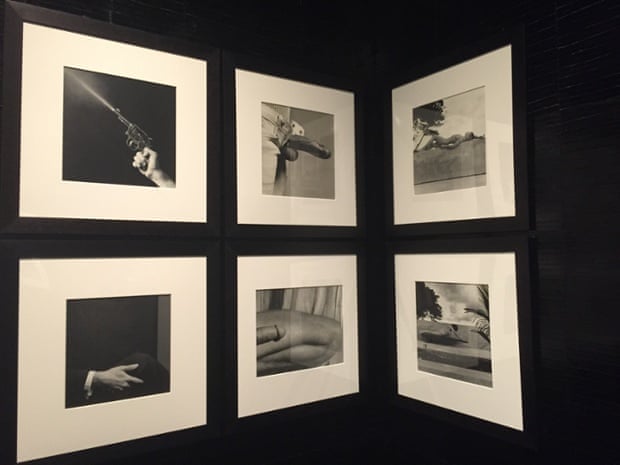

Although it occupies galleries that are too small for close to 100 pieces, the show has been smartly installed. The sequence of works and the conversation about current painting that it presents in real space is one of its primary strengths. It is arranged in largely contrapuntal exchanges between extremes: spare and labor-intensive; little or no color and lots of it; improvisation and deliberation; and riffs on Minimalism and reconsiderations of Expressionism, both abstract and figurative. And in plotting this conversation, Ms. Hoptman makes highly effective use of the narrow, dead-end space at her disposal, dividing it crosswise with walls, including four free-standing ones.

Consequently, artists drop in and out of sight, and different ones are prominent, when you retrace your steps, as you must. The work of Josh Smith, possibly the most rough-edged artist here, is (perhaps deliberately) invisible until you reach the show’s final space and turn around. Mr. Smith’s nine canvases insouciantly sum up the show’s no-holds-barred attitude, tripping the light fantastic with works variously monochrome, gestural and figurative, as well as a kitschy sunset and the artist’s signature, writ goofily large.

The contrasts among artists are sometimes so glaring they seem sure to set even a novice’s mind in motion. At the entrance, the large elaborately textured and tinted, latently Symbolist paintings on paper by Kerstin Brätsch — which suggest masses of rustling silks or feathers — flank a wall of works from which they could not be more different: Joe Bradley’s emblems simply outlined in grease pencil on raw canvas, redolent of children’s drawings. But the rich detail of Ms. Brätsch’s works attunes you to the unexpected subtleties of Mr. Bradley’s bare-bones approach. The rudimentary perpendicular forms of his “On the Cross,” for example, are enhanced by repeated diagonal creases in the canvas, intimating the wrapping of a bandage, a shroud or swaddling.

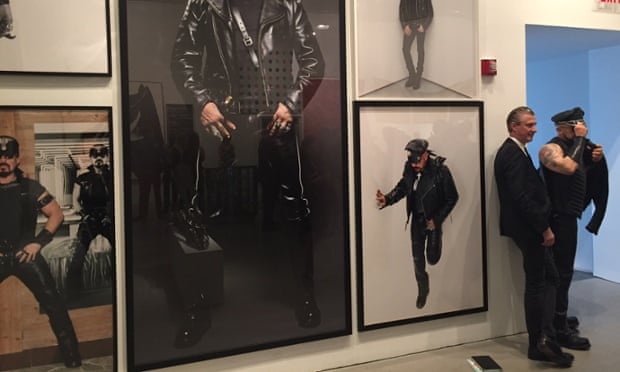

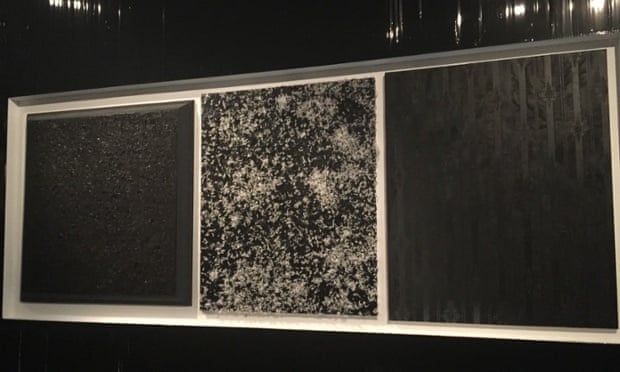

Rashid Johnson’s voluptuous black paintings, whose thick graffitilike marks are scrawled into a mix of wax and black soap with a broom handle, confront the more delicate and colorful improvisations of Michaela Eichwald, which look impressive but more decorous than usual.

After that comes a conversation about carefully but thickly applied paint that is one of the show’s best face-offs. To one side: Mark Grotjahn’s palette knife loops of color, which define a deep space but are also scattered with oblique features, and Nicole Eisenman’s forthright, masklike faces, laid on in thick, textured slabs of color. They recall the early modernist visages of Alexej von Jawlensky, but on a contemporary scale and with references to our political present: a raised (white) fist here, collages of African sculpture elsewhere.

Sometimes the show makes such clear points, you can get the impression that artists or works were chosen to fill slots, to demarcate positions as much as for themselves. You almost imagine Ms. Hoptman going down a punch list.

Interactive? Check: Mr. Murillo has an additional eight unstretched canvases on the floor that visitors can unfold and look at, like rugs at a bazaar.

Minimalism? Check: Matt Connors is represented by an immense three-panel work in sharp, non-primary hues of red, yellow and blue. Purposefully made so tall it can only lean against the wall, it evokes everything from Barnett Newman’s “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue” painting to Richard Serra’s steel plates.

Painting as deconstruction? Check: Dianna Molzan’s piquant explorations of canvas, stretcher and paint improve upon the French Surface/Support group of the 1960s.

Abject-art deprivation and the trendy “de-skilling”? Check. Richard Aldrich’s elegantly offhand works, one of which has strips of painted wood and canvas at right angles to the canvas.

His spare works face the excessive but smooth-surfaced paintings of Michael Williams, whose crazed, partly printed tapestries of color, cartoons and airbrushed lines make the digital and the handmade all but indecipherable. Mr. Williams ends the show on a very promising note.

There’s one way that “The Forever Now” is something of a landmark: Nine of its 17 artists are women. A large-group show that is over 50 percent female is beyond rare and sets a standard for other museums (and commercial galleries) to match.

Less cheering is this demographic detail: With one exception, all the older artists are women, all the younger are men. And only three are not white.

And yet it’s not just about numbers. This show also reminds us that a more open art world allows male and female artists alike to have inflated reputations, which I think is the case with Amy Sillman, Charline von Heyl and Ms. Mehretu. They’re perfectly good painters, but no better than, say, Joanne Greenbaum, Dona Nelson, Sadie Benning and Katherine Bernhardt, any of whom might have disrupted the conversation here a bit more.

Another possibility would have been the irrepressible Mickalene Thomas. It’s great to think of her extravagant depictions of proud black women in this well-done but too-safe show.

It makes you wonder what’s so scary about surveys of current painting.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE