REYKJAVIK, ICELAND — It wasn’t exactly a beach day. It was a chilly, damp November morning with a drizzle that turned intermittently to rain. Björk called it “sniffle weather”; she and a video crew were at Grotta, a lighthouse on a spit of land on the coast here that she has often rented for stretches of isolated songwriting.

The tide and fleeting winter daylight gave her only a few hours to make the video that, if all goes as planned, will turn “Stonemilker,” the first song on her new album, “Vulnicura” (One Little Indian), into the virtual-reality finale of the Björk retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art that opens on March 8.

Björk was, as she has so often placed herself throughout her career, on the cusps of nature and technology, raw emotion and complex artifice. She often calls herself a “pop musician,” but that’s a humble understatement for an artist who, over the past three decades, has constantly experimented with sounds, structures and images around the elemental communication of her gentle, searing voice.

She was a preteenage pop singer — releasing her first album at 12 — and then the frontwoman of the Sugarcubes, Iceland’s celebrated art-punk band. Since 1992, she has made adventurous solo albums that, for all their eccentricities, have been international hits. Working with designers and directors, she has also enfolded herself in the kind of enigmatic, memorable images that made her appealing to MoMA — not least of them the unforgettable swan dress she wore to the 2001 Academy Awards, in which her effigy will preside over the public lobby during the exhibition.

She’s a consistent early adopter of new technologies. To shoot “Stonemilker” in 3-D, 360-degree virtual reality, the director Andrew Huang was using four pairs of sports cameras on a stand, refitted with 180-degree-angle lenses and facing in four directions, with their images to be stitched together later by software. Parts of the prototype were “literally held together with Scotch tape,” Mr. Huang said.

For the video, Björk wore an asymmetrically layered neon-yellow dress and leggings — the color, she told me, of “emergency” — and white platform shoes that made it difficult to clamber over a tall rock wall onto the black stone beach where the camera was set up. There wasn’t much time; by midafternoon, high tide would flood the only road from the lighthouse.

Since the 360-degree capture left nowhere to hide, Björk performed unseen; the crew and observers crouched behind the wall. As she lip-synced and danced, her voice, a string orchestra and a fitful electronic beat poured out of a speaker as she sang, “We have emotional needs!”

“Vulnicura,” Björk wrote on her website, is a “complete heartbreak” album; its songs plunge into the estrangement, separation and self-healing that came with the breakup of her relationship with the artist Matthew Barney. Their daughter, Isadora, was born in 2002. She also has a 28-year-old son. “Usually I don’t really talk about my private life,” Björk said. “But with this album, there’s no two ways about what it is. I separated during this album, ended a 13-year relationship, and it’s probably the toughest thing I’ve done.” (Through a spokeswoman, Mr. Barney declined to comment.)

She added: “You feel like you’re having open-heart surgery, with knives sticking in, so everything is out, and you have this urgency and immediacy. It has to happen right now, that you have to express yourself. And part of it is, you always feel like you belong to another power. It’s not yours, it’s like the universal heartbreak energy current — dot com,” she said with a laugh, “that is taking you hostage.”

The album’s intended release date, in March, was planned to coincide with the MoMA show and a world tour beginning March 7 at Carnegie Hall. But when the complete album was leaked on the Internet, Björk decided to sell her legitimate version online immediately. Her decision “was mostly impulsive,” she said by phone last Saturday. “All the record companies around the world were just stubborn about keeping to the plan. I’m not just, ‘Break the rules to break the rules,’ but it had a strange smell to it. The chances people were going to wait a month and a half were zero.”

“It was a 50-50 thing,” she continued. “What tipped it was also the emotional content of the album. It’s just been really important for me to have it out there. For me psychologically, to put it out in the world and move to the next thing — I think that’s good, and good karma, and good for me and my family, to just move on.”

Throughout Björk’s solo career, her music has merged the worldly and the otherworldly in ever-mutable ways. She has made albums extrapolating from club dance beats (“Post”), constructed almost entirely of vocal sounds (“Medulla”), or shaped by the plinks of harp and music boxes (“Vespertine”). Her 2011 album, “Biophilia,” featured an Icelandic choir as well as one-of-a-kind mechanical instruments, which will be displayed and heard in MoMA’s lobby. “It was important for her to have something of her show that is accessible to everybody,” said Klaus Biesenbach, MoMA’s chief curator at large, who first approached her about a retrospective back in 2000. Because she sees herself as a musician, not a visual artist, Björk didn’t agree to the idea until 2012.

In his introduction to the exhibition catalog, Mr. Biesenbach praises her for “creating innovative forms that cross all channels of our media-driven society.”

On her 1997 album “Homogenic” and, in different ways, on the new “Vulnicura,” Björk sets dramatic string arrangements against electronic beats — though “Vulnicura” is far less rhythm-driven, more rhapsodic, more abstract and more openly desolate. The similar palette may be no coincidence; both albums deal with heartbreak and perseverance.

Writing, for Björk, is largely solitary: “selfish moments” when she gets a chance to reflect. She often writes while walking outdoors, she said, “so it’s not a coincidence that most of my songs are 85 or 90 beats per minute.”

But this serious artist can also cut loose. After countless video takes in the cold, Björk could have called it a day. Instead, she invited the crew and some Reykjavik friends to her home for a wrap party that was also, it turned out, Björk’s slightly belated 49th birthday party. One friend’s gift was a scarf painted with Michael Jackson in Pierrot costume, which had her gushing about the “celebration, that sense of merging with other people” in his music. Then came a club crawl, much of it sound-tracked by her iPod.

First she plugged into the sound system of a cafe-bar near her house: Minimalism, gamelan music. Then the group headed into central Reykjavik and a basement club where Björk and her iPod took over for the D.J., playing Chaka Khan, Bollywood and the avant-pop composer Mica Levi. She hopped out of the D.J. booth to dance on the pool table, rolling across it like something in a vintage MTV video. Around midnight, she led her flock to Prikid, a packed hip-hop club, where she danced nonstop, sang along and downed shots of birch schnapps until nearly 4 a.m. “Best! Song! Ever!” she shouted when Amerie’s “1 Thing” hit the sound system.

“I like to do that properly, go all the way when you feel it,” she noted two days later, when she played the album for me in her home studio. “I like the extremes.”

Her house is cozy and book-lined, with startling touches of nature brought indoors: a spherical chandelier made of white feathers, a stone staircase with a balustrade built from (unendangered) minke whale bones. Her second-floor studio overlooks a seascape panorama: a cone-shaped mountain, a black sand beach, an ever-changing Icelandic sky. As she was about to hit Play on her laptop, she paused. “That cloud is crazy!” she said. “It’s like a fuzzy triangle, and then all the other clouds have definition.” I suggested that it was like her new songs; electronic sounds with indistinct edges are set against the fervently physical, defined strings and vocals.

The songs on “Vulnicura” are both premeditated — Björk writes her own string arrangements — and resolutely unguarded, with Björk’s voice open and exposed. She often kept her first impulses for the lyrics. “I almost didn’t fix anything,” she said. “It’s just got to be this conversation in your head, and if you take it someplace else then it loses the only thing it’s got — that urgency.” The album’s first six songs are a chronology of the breakup: feeling the partnership crumble and, eventually, coming to terms with it. “At the time I was really grumpy, like a teenager, because I couldn’t stand how typical it was. But it is true, when you are going through it, the songs just pour out of you,” she said.

“Weirdly, I think the survivalist in me kicked in. When you’re going through the most difficult things emotionally, the scientist kicks in to try and make sense of it all. Part of me wants just to hide it, and part of me is going, ‘No — this could be a document of the heartbreak of the species, and could even be helpful to someone.’”

Björk wasn’t looking forward to recording the songs. Although she enjoys the process of building and editing music with software — she compared it with knitting and embroidery — it had taken her three years to finish “Vespertine” because she was painstakingly constructing beats on her own. On previous albums, she had done most of the music but brought in collaborators to handle the most complex parts. “I could finish all my albums myself and do it on my own,” she said, “but it somehow doesn’t agree with my philosophy. I would feel it would be too inbred.”

Luckily, while writing “Vulnicura” in 2013, she heard two songs by Arca: Alejandro Ghersi, a 25-year-old electronic musician from Venezuela who had grown up on her music and who has made tracks with Kanye West and F.K.A. Twigs. She invited him to work with her in Iceland, and he ended up co-producing seven songs and programming for the other two. Another electronic musician who has darker sounds on his mind than dance beats, the Haxan Cloak (a.k.a. Bobby Krlic), mixed it.

Arca will be touring with Björk, along with a 15-piece string orchestra and the percussionist Manu DeLago, whose specialty is a steel drumlike instrument, the hang. “She’s a musician of the highest order,” Arca said via Skype. “She would be very, very precise, but it also would be accompanied with a lot of freedom.”

Both Arca and Björk said that he started out largely executing her ideas — she called herself a “bossy back-seat driver”— but their collaboration deepened. In the studio, he said, he sometimes “felt like a kid. We would just trade stuff back and forth — dancing a lot, laughing hysterically.”

The bleakest, bravest song on “Vulnicura” is “Black Lake,” which is dated in the album booklet as “2 months after” the separation. “My soul torn apart, my spirit is broken,” Björk sings, and the strings hover behind her in open, austere chords. When verses end, the chord sustains, lasting longer than the verse. It’s harrowing and deliberate.

“We call them the freezes,” Björk said. “At the time, I couldn’t put together one logical thought. You’re just stuck in pain, you’re stuck in unbearable pain, and you can just about express yourself and then you’re just stuck in the pain. You’re paralyzed.”

Yet as Björk recorded the album, “Black Lake” took careful technological shape. Along with “Stonemilker,” it is part of the “new commission” of the MoMA exhibition. At the sessions, each of the 30 string players was individually miked; MoMA is building a room with an array of speakers that will allow visitors to approach each track separately for a spatial experience of the music.

In the three years that Mr. Biesenbach and Björk have been working on the exhibition, she has grappled with the idea of “how do you hang a song on a wall?” They were drawn to the idea of songlines, the indigenous Australian tradition in which songs and images become maps. The question became, “How could you move in space, steered by sound and music?” Mr. Biesenbach said.

The show will have visitors — only 100 at a time — wearing headphones and walking through each of Björk’s adult solo albums in a room of its own, looking at costumes and videos and hearing a song through location-based triggering that will place them within the recordings. The audio guide will also include a fabulistic tale of Björk’s itinerary, written by her and a periodic collaborator, the novelist and poet Sjon, and narrated by Björk and an Icelandic director and actress, Margrét Vilhjálmsdóttir. For exhibition visitors, voices and music will demand as much attention as costumes and videos. “It will be some cacophony of sound,” Björk said. “There’s obviously some risk involved. But if it’s not dangerous, it’s not worth doing.”

]]>

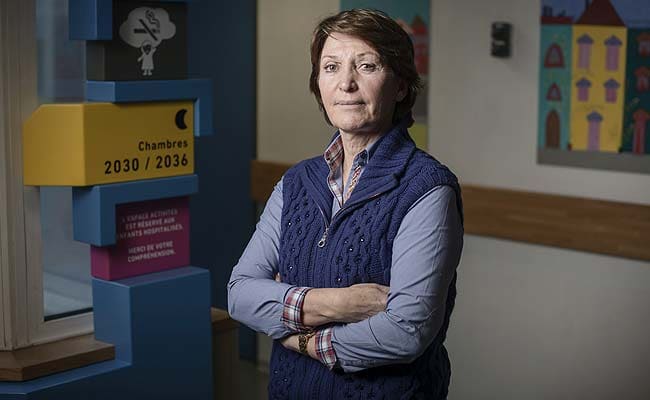

MARSEILLE, FRANCE: Since Marina Picasso was a child, living on the edge of poverty and lingering at the gates of a French villa with her father to plead for an allowance from her grandfather, Pablo Picasso, she has struggled with the burden of that artist's towering legacy.

MARSEILLE, FRANCE: Since Marina Picasso was a child, living on the edge of poverty and lingering at the gates of a French villa with her father to plead for an allowance from her grandfather, Pablo Picasso, she has struggled with the burden of that artist's towering legacy.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE  ENLARGE

ENLARGE

SAM GILLIAM

SAM GILLIAM ELAD LASSRY

ELAD LASSRY JOHN MASON

JOHN MASON JONAS WOOD

JONAS WOOD RASHID JOHNSON

RASHID JOHNSON MARY WEATHERFORD

MARY WEATHERFORD RICKY SWALLOW

RICKY SWALLOW LESLEY VANCE

LESLEY VANCE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE  ENLARGE

ENLARGE  ENLARGE

ENLARGE  ENLARGE

ENLARGE  ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

ENLARGE