A man who makes films about people who never stop moving would seem unlikely to set down roots. Yet the artist Doug Aitken has built himself a house in Venice, Calif., that is too much fun to leave — even to go to the nearby studio where he created “Black Mirror,” his film project with Chloë Sevigny as a nomad who spends her days checking into and out of anonymous motels.

The house is the world’s first temple to “Acid Modernism,” the aesthetic the California-born Aitken conceived for himself and Gemma Ponsa, his companion of the last six years. “The goal was to create a warm, organic modernism that’s also perceptual and hallucinatory,” he said of the design. “We thought that would be a wonderful environment to live in.”

Acid Modernism: it’s an apt term to characterize a modest, functional home where the ground-floor walls and curtains have been silk-screened to simulate the hedges growing outside the windows, the sky-lighted staircase is lined with angled mirrors that turn the passage into a dazzling kaleidoscope and the light fixture that illuminates the vintage Western-Holly kitchen stove looks as if it’s wearing a toupee. The toupee is actually a cluster of air plants, tropical ferns that feed off the moisture from Ponsa’s cooking.

“For Doug the house is more like an artwork,” said Ponsa, an obsessive foodie who met Aitken in her native Barcelona. She has claimed one of the two upstairs bedrooms as an office where she is developing a Spanish-language cooking show for television. “For me,” she said, “this is an organism — my dream house, where the materials and the architecture don’t intrude on the nature around it.”

And it’s true: the house does not so much intrude on its surroundings as collaborate with them, in what Aitken calls a “living experiment” based on “concepts and ideas,” a phrase that often recurs in his speech. “There’s really no differentiation between the work I make and the world I live in,” he said.

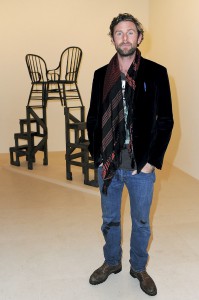

A sunny 6-foot-1, Aitken is known for staging large-scale public “Happenings” — theatrical entertainments involving farm auctioneers, gospel singers, a drum corps, dancers, a bull-whip-snapping cowboy and food served on “sonic” tables. But mainly his work takes form in sculpture, photographs and books, as well as high-definition silent films like the poignant 2010 short piece “House.” In it an elderly man and woman (Aitken’s parents) sit motionless at a plain wood table that Aitken designed. After a few moments, the walls around them start to crack, the windows shatter, the chimney crumbles, and plaster rains down, but they never avert their eyes from one another, even when the roof falls in.

These were not special effects. The house in the film is the cramped, 100-year-old cottage where Aitken lived for 12 years, until it threatened to collapse. “What you see in the film’s last image is everything leveled, just raw earth,” he said. “At that stage we found ourselves asking how we move forward.”

The creation of the new house, which sits on the same footprint as the old one, proceeded with similar questions: “How does one live the outdoor-indoor life? How does one work with ideas and culture, with the light, the wind, the atmosphere, the foot traffic in this specific place? How do you frame the world around you within the architecture?”

For Aitken, “These things that we take so much for granted — a chair, a table, a light — shape what you make. . . . And you want to make places you can share, where you can collaborate and have people over, and have an experience.”

The new dwelling is taller and more spacious, with bay windows that jut like balconies from the second story and outer walls of mismatched wood partly reclaimed from its predecessor. What was once a detached garage is now a split-level studio and guest room set off by amber and yellow windows that create a warm glow within. A white-walled projection room takes up the lower level. The sleeping loft has a full bath hidden behind a panic-room door disguised as a bookcase that opens by pulling a fake volume of “Ulysses” from one shelf. “It really looks like a book!” Ponsa said, laughing.

On a deck raised above a roof as flat as Buster Keaton’s hat is an edible garden with a view of the Pacific Ocean a block away. Succulents growing in concrete planters at the bottom of the prismatic staircase drink in the sunlight pouring down from above and into the core of the house. And at certain times of day, the living room windows appear to melt away, dissolving the painted walls into the greenery beyond them.

Aitken has created a similar illusion with “Song 1,” a new film projection for the circular exterior walls of the Gordon Bunshaft-designed Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. The projection, which had its premiere on March 22 and runs through May 13, appears to dematerialize the U.F.O.-like building into pure light and sound.

The effect is only one example of ideas that turn up in both his house and his art. “I think that living with a lot of plants inspired Doug’s ‘SEX’ work,” Ponsa said, referring to Aitken’s marquee-like sculpture of block letters that spell out the title word and contain a terrarium of local flora and driftwood. In 2009, he erected a wood and curved glass “Sonic Pavilion” at Instituto Inhotim, an immense privately owned art park near Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The pavilion sits over a deep cut in the earth where Aitken and his studio crew buried microphones sensitive to vibrations caused by the rotation of the planet.

Aitken took that concept further in his house, by embedding nine geological microphones in its foundation. They amplify not just the groan of tectonic plate movements but also the roar of the tides and the rumble of street traffic. Guests can listen in on this subterranean world without putting an ear to the ground. Speakers installed throughout the house bring its metronomic clicks and extended drones to them whenever Aitken turns up the volume. “It’s very easy to lose track of the environment around you, to lose touch with the present,” he said. “I wanted the house to help bring me back to the moment that is.”

A half dozen other microphones installed under the staircase make it possible to play the steps like a percussion instrument. Aitken even keeps lightweight mallets on hand for those who want to pick out a rhythm, or they can also use their feet. And when they sit down for one of Ponsa’s meals, they can play the suspended marble surface of the “sonic” dining table. “This is a great house for an insomniac!” he said. (Though in truth he looks every bit the well-rested surfer that he is.)

Still, Aitken insists that “it’s not a radically avant-garde house. It’s not glamorous. But there’s nothing more stimulating than living in an environment that I feel free to experiment with. Come back in a year and there might be new developments.”

“Is it the art or is it the hype?” I’ve been asked this question so many times it makes me ill. It always comes from those who don’t look at art and are trying to explain why they don’t buy it. In a skeptical tone they slip me this line on a regular basis. “Yes,” I tell them with a smile, “it’s all a fraud. These contemporary art stars are all phonies and fakes, it’s the fancy galleries promoting this stuff and you’re the smart one who figured it all out.” But what I’m thinking is, “Cretin, you don’t understand a damn thing about art.” But now even most art believers have to admit that parts of today’s art scene have indeed gone too far. Yet when I spelled it out for the world in my satire of the Art Basel Miami Beach fair last December, I was attacked by many insecure pundits, advisers and dealers who felt threatened by the words. But forgetting the whiners, it’s what everyone was and is still talking about. Just last Sunday 60 Minutes ran a Morley Safer-hosted exposé bashing the fair, highlighting the hype in order to suggest that contemporary art is no more than a marketing circus. We can’t really blame old Morley Safer—he’s just another blowhard—but I was shocked to see one respected dealer, Tim Blum of Blum and Poe in Los Angeles, play right into Mr. Safer’s canard. “We’re from Hollywood, this is theater, only theater,” he said when asked about art prices. “It’s the wild west … competition is vicious … when the question of value comes up we drop the subject.” Mr. Blum misspoke—and that’s regrettable because, let’s face it, when the hype booms louder than the art, the art world invites the philistines right to its gates.

“Is it the art or is it the hype?” I’ve been asked this question so many times it makes me ill. It always comes from those who don’t look at art and are trying to explain why they don’t buy it. In a skeptical tone they slip me this line on a regular basis. “Yes,” I tell them with a smile, “it’s all a fraud. These contemporary art stars are all phonies and fakes, it’s the fancy galleries promoting this stuff and you’re the smart one who figured it all out.” But what I’m thinking is, “Cretin, you don’t understand a damn thing about art.” But now even most art believers have to admit that parts of today’s art scene have indeed gone too far. Yet when I spelled it out for the world in my satire of the Art Basel Miami Beach fair last December, I was attacked by many insecure pundits, advisers and dealers who felt threatened by the words. But forgetting the whiners, it’s what everyone was and is still talking about. Just last Sunday 60 Minutes ran a Morley Safer-hosted exposé bashing the fair, highlighting the hype in order to suggest that contemporary art is no more than a marketing circus. We can’t really blame old Morley Safer—he’s just another blowhard—but I was shocked to see one respected dealer, Tim Blum of Blum and Poe in Los Angeles, play right into Mr. Safer’s canard. “We’re from Hollywood, this is theater, only theater,” he said when asked about art prices. “It’s the wild west … competition is vicious … when the question of value comes up we drop the subject.” Mr. Blum misspoke—and that’s regrettable because, let’s face it, when the hype booms louder than the art, the art world invites the philistines right to its gates.