|

|

New York’s highest court has decided to review a recent ruling that could force the state’s auction industry to end its longstanding practice of keeping sellers’ names anonymous.

Most sellers in the New York auction market remain anonymous, and auction catalogs typically reveal little more than that a work is from a “private collection.” The court did not rule that auction houses had to publicize widely the name of a seller, only that buyers are entitled to know it. Buyers — themselves often people who anonymously sell items at auction — have seldom complained about the practice, while sellers have come to expect their identities to be shielded.

But in October, in a dispute over the sale of a 19th-century silver-and-enamel Russian box, a four-judge appellate-court panel unanimously ruled that state law has long required that buyers be given the names of sellers in postauction paperwork for the deal to become binding.

Many art-law experts say the decision, if upheld, could significantly change the way the auction business is conducted in New York State.

“As of now you can back out of any transaction where the name of the seller is not provided,” said Peter R. Stern of McLaughlin & Stern, a Manhattan lawyer who represents dealers, collectors and auction houses and was an outside counsel to Sotheby’s.

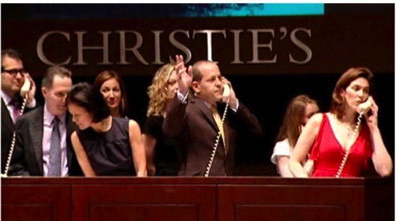

The lawyer for the auctioneer in the case said Christie’s had inquired about submitting a brief when the New York Court of Appeals, which last month announced its intention to review the case, takes it up this spring. The auction house declined to comment.

Jonathan A. Olsoff, director of worldwide litigation for Sotheby’s, said that auction house viewed the decision as “narrow and technical” and that others were overstating its impact. Although fine-arts sales are the highest-profile auctions in the state, the ruling would also affect the sale of other items, like heirlooms, vehicles and livestock, which are also typically auctioned anonymously by hundreds of companies every week.

Anonymity is often prized because it protects personal privacy and allows institutions quietly to sell items from their collections that they no longer need. In some cases it can also cloak the embarrassment of debt or help sellers avoid setting off family conflicts over the disposition of inherited assets.

“Anonymity should not be seen as an abuse of the law,” said Christine Steiner of Sheppard Mullin, a Los Angeles law firm. She is a former Maryland prosecutor who has represented sellers from all income levels.

The ruling came in a case involving an auctioneer in Chester, N.Y., William J. Jenack, who sold a Russian antique in 2008 for $460,000. The piece, a czarist box made by I. P. Khlebnikov, a Fabergé contemporary, depicted aristocrats feasting on a roasted swan. Mr. Jenack said the top bidder, Albert Rabizadeh of Long Island, refused to pay after “grumbling about the price.”

Mr. Jenack sued for payment and won, but the decision was overturned by the appellate court when Mr. Rabizadeh challenged the transaction because the seller had not been identified in the postsale documentation.

In arguments last year before the appellate court lawyers for the auctioneer said that revealing the seller would overturn centuries of commercial practice and badly burden the industry. But the appellate panel, citing New York’s anti-fraud statutes, was unmoved.

“While it may be true that auction houses commonly withhold the names of consignors,” Justice Peter B. Skelos of the appellate division said in his ruling, “this court is governed not by the practice in the trade, but by the relevant statute.” He said the law “clearly and unambiguously requires that the name of the person” selling the item be included in documents provided to the buyer.

If the ruling stands, some experts say, a buyer denied a seller’s name would have the right to walk away from any purchase, as happened in Mr. Jenack’s case.

Through his lawyer, Daniel R. Wotman of Great Neck, N.Y., Mr. Rabizadeh declined to comment, but Mr. Wotman said, “Auction houses and consignors need to comply with the law.”

Benjamin Ostrer of Chester, the lawyer for Mr. Jenack, said the ruling represented “a wholesale invitation to have people renege.”

Mr. Olsoff of Sotheby’s disagreed however. “The decision,” he said, “deals only with the evidence that is required if an auction purchaser defaults in paying and is sued by the auction house.”

Several lawyers said auctioneers could try to resolve issues by having buyers agree to anonymity in writing before bidding. But Leila A. Amineddoleh, an expert on art law at Lombard & Geliebter, said she would discourage buyers from signing such a waiver, especially because the seller’s identity can aid with provenance questions and enhance the future value of an item.

She predicted that if the ruling is upheld, some auctioneers would lobby in Albany for legislation to exempt them from disclosing the seller.

Nicholas M. O’Donnell, a lawyer with Sullivan & Worcester in Boston who writes that firm’s Art Law Report, said the ruling also allowed winning bidders to sue auction houses for sellers’ names. “Once the gavel falls there is a binding agreement that cuts both ways,” he said. “The implications are very far-reaching.”

Mr. Jenack said fellow auctioneers worry that their clients would sell in other states where privacy is protected.

Lawyers said they had not heard of court rulings in other states that appeared to restrict the granting of anonymity to sellers at auction.

One person with a strong interest in the case is the box’s seller, Jonathan A. Thompson, 70, of Greenwich, Conn. He said anonymity was the last thing he cared about when he put the family heirloom up for sale in 2008.

He ended up with $50,000, he said, when the box was resold at auction in 2010, not the money he once stood to make, but far more than the $5,000 value first put on the box when Mr. Jenack originally advertised it.

“I didn’t ask to be anonymous,” he said. “I didn’t think at all about it.”

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TS580_0711sc_DV_20120711170034.jpg)